Investments in school health are a strategic win for a country’s education and health sectors - and more critically - a win for children and adolescents.

For the health sector, schools represent a cost-effective platform for reaching school-age children with the health and nutrition interventions they need to achieve their potential. For the education sector, delivery of health and nutrition services ensures that a child’s poor health is not a bottleneck to learning, growth, and cognitive formation. For these reasons, investments in school health and nutrition are synergistic and essential to other educational investments focusing on quality and access. Moreover, school health sets the stage for children to thrive and become transformative agents in their communities.

Multi-sectorial Coordination: A School Health Mission

Discover the power of coordination in implementing school health and nutrition interventions. Play this interactive game to see how you can make a difference!

Curious how to advocate for school health and nutrition interventions? Check out our toolkit on school health and nutrition: a set of multimedia microlearning products for health and education policymakers, practitioners and donors.

What is School Health?

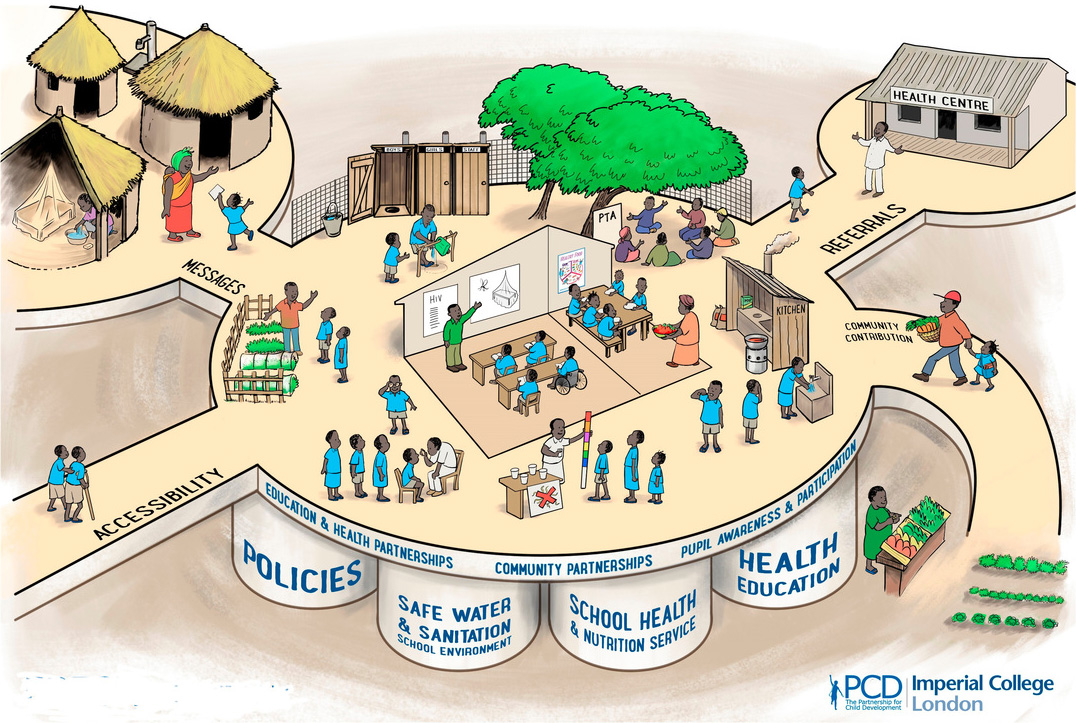

Broadly we can think about school health in terms of what is required for children to be healthy. One of the most well-known frameworks for making school health concrete and parsing it into major component areas is UNESCO’s Focusing Resources on Effective School Health (FRESH) framework. In this framework, there are four pillars of school health:

- Policies. National, sub-national as well as school policies that make children safe and signal a commitment to every child’s health.

- School environment. Settings that are safe and free from hazards and that have well-maintained sanitation infrastructure.

- Services. Routine health services delivered through schools that are appropriate and adequate for the students’ needs. These services vary by setting and examples include school meals, deworming, and routine vision and oral screenings, HPV vaccination, among others.

- Education. Providing students with age-appropriate information to empower them to take ownership over their health and well-being.

What We Know About the Benefits of Strong School-Health Programs

What We Know About the Benefits of Strong School-Health Programs

Quite simply, healthy children learn better. For instance, certain conditions that are prevalent among school-age children and adolescents can impair cognition, attention span, and learning. To take one example, the average IQ loss for children with untreated worm infections is estimated to be 3.75 IQ points per child, and the average IQ points lost due to anemia is even higher. The good news is that most of these conditions are easily treatable. School-based health interventions in areas where these conditions are prevalent could result in 2.5 additional years of schooling for affected children. Plus, an integrated package of interventions can further maximize impact.

Nearly every country offers some form of school-based or school-linked health service to improve the physical health and nutritional status of school-going students. Approximately one-in-two children receive a meal in school each day.

Although the relationship between healthy children and able learners has been well-established, in practice many children remain inadequately supported. Annual public spending for health ages 5-20 is less than 3 billion USD. Because health is a prerequisite for learning, the substantial educational investments likely fail to realize their true dividends as inadequate health serves as a constraint to learning and development.